|

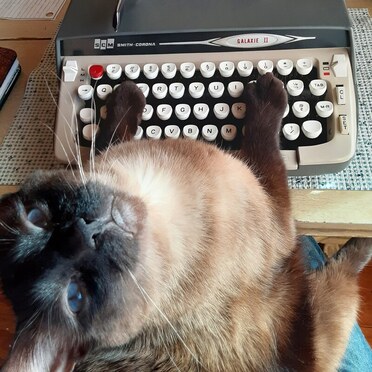

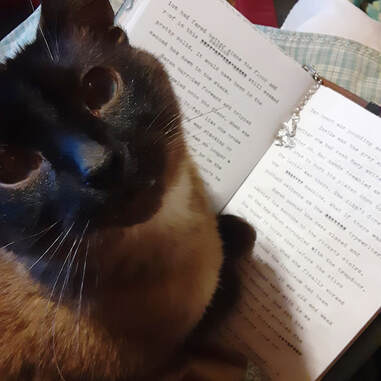

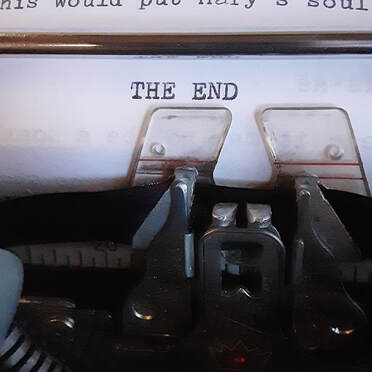

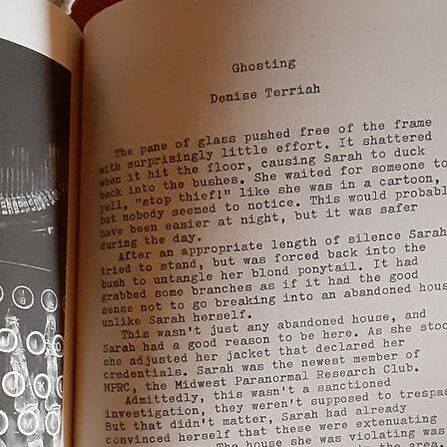

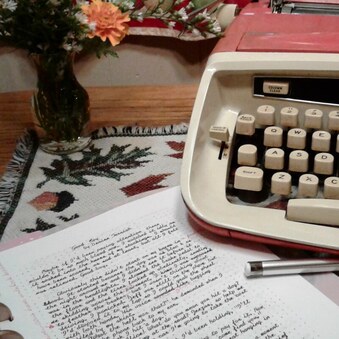

If this blog were a place it would need a good dusting. These are some strange and terrible times we're living in right now. Between the pandemic, institutional racism, radicalized home-grown terrorism, and eventually an attempted coup of the United States government. It's had me down. Way down. So very down. As a dystopian author, it's hard to watch the genre spill so effortlessly into our everyday lives. Admittedly I withdrew most of my online presence, and social media. It's not a particularly nice place out there. Pulling back and slowing down seemed like the way to deal with this. So I took a break. I planted seeds. I baked. I watched way too much news. I built things. I raised animals. I sewed. I knitted. I waited for the storm to pass. No, the storm hasn't passed. Thunder rolls in the darkened sky. But I think it's time to clear away the cobwebs because it could honestly be years before the storm has passed. At least with a new administration, I see hope as a dim sliver on the horizon. I don't think the next few years will be easy. But we will all continue to do what must be done. What am I doing? I'm choosing to poke my social media back to life and admit that I haven't lived in complete stillness. I have some writing projects to come. Some moving much more slowly than I want. But I realized I've never even mentioned that I had another short story published. While I was watching the storm roll in, a call for submissions was put out for a new book called "Backspaces: Typewritten Tales of Time Travel." from Loose Dog press. I was immediately interested. They put out two books in a series called "Cold Hard Type" in 2019 that were a wonderful combination of short stories and poems about post-digital worlds and typewriters. These were: "Paradigm Shifts: Typewritten Tales of Digital Collapse" and "Escapements: Typewritten Tales from Post-Digital Worlds" Clearly dystopian worlds and typewriters are absolutely my thing. As if that wasn't enough, they made Cold Hard Type I & II even better, the stories and poems are typed up by the authors on their own typewriters and then the typewritten images are scanned and put into the book! Before I read any of it I flipped through it over and over just looking at the various typefaces. How fun. I didn't submit anything to the first two books because I hadn't found them before submissions were closed. I was giddy about the possibly of taking part in such a fun project. Cold Hard Type III was supposed to be about time travel and typewriters. Surely I could come up with something. Sorry, we. I meant WE could come up with something. So we sat down to my beautiful 1965 Smith-Corona Galaxie II and went to work. After a couple of false starts a ghost story began to coalesce, and we managed to write up a first draft. Then a second, and a third. We edited until we were sick of looking at it. Somewhere in the early days of the pandemic we finished and submitted the story, "Ghosting." To my great delight the work was accepted. After a solid rewrite and some more editing we were ready to type up the finished story on our Brother Charger 11 The finished story can be found in Cold Hard Type III: Backspaces. It's called "Ghosting" by Denise Terriah. Check it out if you get a chance.

0 Comments

Sit with me and have a virtual cup of tea. We need to talk. I'll start by telling you I haven't been out in public since March 15th. Partially because I'm dead afraid of facing this virus while I battle what's already wrong with me. Mostly because I care about human life. I've never before been in a situation where I can save lives by doing nothing.

Let that sink in for a moment. Doing nothing can save human lives! I've already talked to a huge pile of people who just keep telling me they aren't afraid of getting the virus. That's fine, but it's not about them. It's about keeping the vulnerable among us alive. If we can keep the number of new cases low enough, we won't completely overwhelm the medical system, and people won't have to die just because there aren't enough ventilators, or medicine to keep them alive. How hard is it to stay home unless you are a vital worker? My husband is a vital worker. He repairs water wells. He has to go out in public, and interact with people, and surfaces. People need water. What that means, as his spouse, is that I come in contact with those people, and anyone they have come in contact with, and anyone those people have come in contact with. Scary right? What that means is I have to consider myself a carrier. I need to stay away from others as if I am already sick. Not because I'm afraid of getting sick, but because I could kill your grandmother, or your mother, or your uncle, and I don't NEED to. I'm an author. I can do my job from my desk at home. I don't need to go and spend time with friends. I don't need to go to the store. I can just stay where I am. There are a lot of people who can't do that. They are vital workers, or too poor to miss work and still feed their family. They have my respect and my sympathy. But to everyone who is not in that situation; to everyone who is working from home; to everyone who doesn't have to leave their house: don't do it! Don't make five trips to the grocery store this week. Don't wander around and shop because you're bored (you can do that online.) Don't gather with friends and neighbors. Wear your pajamas all day. Binge watch a show you've been meaning to see. Deep clean your house. Don't clean your house. Learn to knit. Whatever you do, do it at home. Stay home because you don't want to get sick. Stay home because you might be a carrier. Stay home because in doing so, you may save a life, or even dozens. I'll admit, I'm picky. I expect an awful lot out of my appliances. For instance, I like them to work. Just before Thanksgiving my gas cookstove stopped working...again...for the second time this year. The oven refused to heat up, and the button that adjusted the temperature required you to rub next to it in little circles to adjust it. I had the stove a little more than 10 years and had to have it repaired countless times. A ten-year-old stove...of course it stopped working. How can you expect something to last for over a decade? I think I did already mention I expect a lot out of my appliances. Thus began the search for the perfect stove. I started at the store, with a list. I've always hated electric stoves, so it had to be gas. I'm a practical woman. I want us to be able to cook when the power goes out. Granted, that doesn't happen very often, but we are quite a ways outside of town. My failed stove had a gas oven, controlled by electronics...which failed over and over again. What the stores had for sale were just more of the same. No thanks. At least now we knew we were going to buy something pre-owned. That is the more eco-friendly option anyway. My long-suffering husband and I started looking through the adds for pre-owned stoves and I drooled over the gorgeous old 1950's models but, I used to rent a place with a stove from the 1960's with a pilot light that always went out. It required a screwdriver to get at the pilot light and filled my apartment with gas regularly. So to make this an insane amount harder, I decided no electronic oven temp controls, and no pilot light. We did find a brand called Unique that makes them new, but after looking at the antique stoves I also wanted something beautiful, and the Unique brand stoves were just utilitarian, modern stoves. Eventually I gave up, I had the flu, and just couldn't deal with my own insane restrictions. My husband however didn't give up. He found me the best surprise I could have hoped for. He continued showing me beautiful things. Eventually he found a stove that met all my insane demands. Just as importantly for me, it was also insanely beautiful.

Oh, and until I had a warming shelf, I didn't realize how useful a warming shelf is. Why did we stop putting warming shelves on our stoves?

The next "issue" is the oven. The actual temperature of the oven is different then the dial says, but that was easily bypassed with an oven thermometer. Problem solved, much cheaper than the hundreds of dollars my last oven regularly required to reach the right temperature. Every single day I can't get over how well this stove works. Only one thing reminds me of it's age: the shutoff valve we installed so that we can be sure it was safe in our home. Sorry, I'm just not very trusting. It doesn't seem to have any issues, but I figure it's better to be overly cautious.

Why not keep looking back on things that I got to have fun doing. I didn't write any blog posts nearly the whole month of November or December due to a brutal flu. I don't know what it was, but it was out for my life. Thankfully I eventually beat it into submission but, in it's wake, I'm still trying to catch up on all the wonderful things that happened that I failed to blog about.

"Good Boy" is horror/fantasy short story that revolves around the myth of the black dog. I enjoyed getting to push myself to try short story writing. I've never had an easy time telling a short story (just ask anyone whose ever had a conversation with me.) December 14th was the release party for "Ladies' Night." Check me out: I was dressed, out of bed, and able to speak. Admittedly I ended up mute from the flu again just a few days later. But, I got to keep my voice long enough to read my short story to the crowd. As a bonus I got to listen to some of the talented poets who had poems published in the same anthology. Now I need to get back to my other projects which include two novels (which are dragging along so slowly) and at least one more short story.

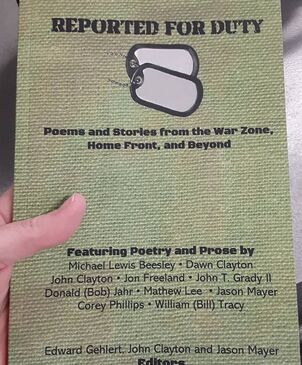

Some very big things happened in the last months of 2019 that I let slide by without even mentioning them on my blog. I know. These things are important. I should have gotten them on here, but this one honestly makes me feel like a bad friend. You heard me, I'm a bad friend. Sorry Mike. I've known Mike since we were teenagers, and he's wanted to be an author as long as I've known him. For anyone wondering...I'll just say it's been more than just a few years. But, when he got his first short story published in a book put out by Happy Duck Publishing (which published my novel As It Ends.) The book is: Reported for Duty: Poems and Stories from the War Zone, Home Front, and Beyond. I failed to shout it from the rooftops. This book was published in November 2019. I've let two months go by without bragging on my blog that my friend Michael Lewis Beesley had his story "The Diagnosis" published.

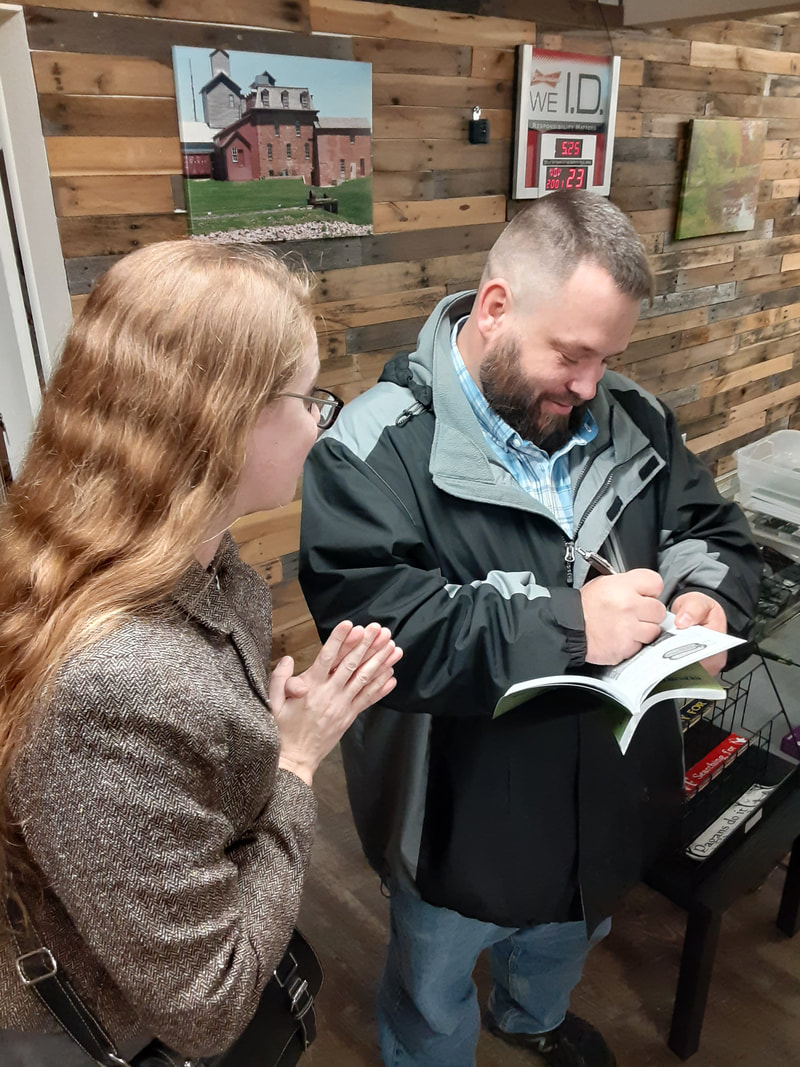

"That's not fair!" I hear you gasp. "Why do you deserve to have the first book he ever signed!"

I'll tell you. Because, as his friend, I took my job very seriously. I nagged him relentlessly until he submitted it to the publisher. How annoying was I? Only Michael Lewis Beesley can tell you the answer to that, but I'm sure it was pretty darn annoying. He submitted a story to a publisher just to get me to leave him alone. You're welcome buddy. I can't wait to snatch up the first signed copy of your first published novel as well. I have a confession. I didn't make a New Year's Resolution. I probably should have. I have a lot of things I want to improve on. I want to write a thousand words every day. I want to be more motivated to write my blog posts on a regular basis. I want to devote more time to my social media presence to improve my visibility as an author. I want to finish my current novel. I want to write a few short stories. I want to finish the sequel to my first novel. I want to have friends over more often. I want to start more projects around the farm. I want to tackle some major building projects. I want to get more herbal research done. I want to grow a bigger assortment of herbs. I want to cook from scratch more. I want to do more canning. I want to watch the news less. I want to lose weight. I want to be more active. I want work towards zero waste. I want to go plastic-free. I want to improve my carbon footprint. I want. I want. I want. See how hard it would be to make one actual resolution? I have a lot of things I want to focus on this year. I'm sure I'm not the only one with such a long list. So, I guess if I had to pick just one thing to change, it would be to forgive myself these many perceived shortcomings and just do what I can do. I can't hope to do more than that and not drive myself absolutely crazy.

I wish you all the peace and fortitude to stick to your own resolutions! As a writer I've been stuck. Not just a little stuck either. I've been really stuck. There's been a lot of changes in my life lately, and all the noise has edged my creativity away. Like pushing my plate across the table. Nope, I'm too full of all these other things to be able to focus. Focus is the important word. I feel like I'm five people trying to live in one head. It's been so loud in here. I've been beyond mere writer's block. I hadn't been able to write, or draw, or blog. I spent hours some days just staring at blank paper. I carried around a notebook to make sure I wasn't just missing my chance to make notes. I tried writing at different times, with different materials, different typewriters, different pens, I even tried writing on the computer. I sat at my desk, in my bedroom, at the dining table, on the porch. Nothing. I learned how far I needed to go, and I mean that quite literally. I've figured out how to write when I'm stuck right now, and my trip was noteworthy. I went out into the middle of the woods. Away from my house, away from chores, away from responsibilities, away from electricity, away from noise, YouTube, Netflix, Facebook, Instagram. Just me and one of my typewriters alone. At first it was magical. I'm working on a dystopian novel, several actually, and sitting in the solitude of the middle of the woods in a tent was pretty much the perfect way to bring myself into a post-collapse-of-society world. A slow trickle of words found there way on the paper in front of me. I stretched and breathed on my cold fingers as ideas started coming to me. I pulled my stocking cap down tighter and hunched in my coat as dialogue flowed from my fingertips. I jiggled my feet to keep my toes from going completely numb as plot points and story line appeared on the paper in front of me. Why didn't I do this before? I stopped and went for a walk to loosen my shivering muscles and try to warm up a bit. Once I'd warmed myself up and had gotten my fill of beautiful fall colors I headed back to the tent I'd set up and sat back down to my writing. The daylight dimmed but I pushed on, even as my glasses fogged with the warmth of my breath as I leaned in to squint at the words in front of me. I had to light my oil lamp before it was fully dark, I listened to crows cackling as the sun disappeared. Soon the coyotes yipped and howled in the hills around me. Their din had no competition because it was too cold for crickets, frogs, and cicadas to sing an evening song. I continued writing even after it was so dark I had to hold my lamp up to my paper just to see what I had typed. The steady clacking of the keys kept me from noticing as 'it' crept closer. A loud crash snapped my head up and froze my fingers on the keys. Footsteps edged closer to my tent as if an enormous lead-footed moth was being drawn to the flame inside. I thought briefly about calling out, but what if it wasn't just an animal? What if it was a man? I was on my own private property. Anyone willing to be out here was clearly unbothered by the idea of laws. If I made no sound I was nothing but a lump in the light wearing my thick coat, with my long hair tucked in. I could be assumed to be a man. Something that's slightly less frightening to be in the middle of the night with some possible criminal roaming in the darkness. Not that men don't get assaulted, it's just that men are more likely to be seen as dangerous. Obviously even by me. I wasn't particularly afraid of some wild woman covered in mud with leaves in her hair wandering in the night outside my tent. Heck, I'd probably invite her to hang out. A branch snapped, and more dead leaves were destroyed under the weight of whatever was outside my tent. As if my mind wasn't already racing, my brain picked that exact moment to tap me on the shoulder and remind me that a couple had been found dismembered in a clay pit less than a mile from this location. If the killer had been caught I'd never heard about it. I looked over and my dog (who had been sleeping tucked under a blanket on his bed in a corner.) was standing at attention next to me. His hair stood out wildly on his shoulders and all the way down his back. He stood in his perfect silence that I think of as 'attack stance.' He worked as security staff at a warehouse I used to work in. He's retired now, but he's still over one hundred pounds of muscular beast, with big teeth, who is tall enough to lay his head on the kitchen table while on all fours. The sound advanced to within ten yards of the tent and I still couldn't decide if it was the plodding footsteps of a man dragging his feet through the leaves, or a deer, which was not really less dangerous since only thin cloth stretched between us, and mating season had just begun. From my own experience this was the one time of the year deer were more likely to run at you, than away from you. My dog made eye contact then advanced at the wall of the tent barking his warning. My dog has foiled a robbery, possibly two, but has never actually hurt a person. I held up my hand for his silence which he gave me. The footsteps had their turn to freeze in their tracks. Now all of us were sitting perfectly still waiting to see what the other planned. I was no longer just a possibly-armed-man, but now a large dog had made himself known. This is about the time that I started sending texts to my husband letting him know that if they found my dismembered body in a clay pit; that I love him and the kids very much. Naturally he assured me he'd be out there as soon as he could. Five tense minutes later the footsteps started moving away from the tent, which was a relief, but then they began making a large circle around the tent which expunged my sense of relief. I felt like I was being stalked. They eventually made their way back to the south side of the tent where they had started, and we sat again in tense silence. The footsteps moved towards us again and my dog began a growling snarl that made the few hairs that weren't already standing to attention on the back of my neck take notice. This was too scary for my new acquaintance: Footsteps. I didn't blame Footsteps, I'd have taken off if that the sound was directed at me. Footsteps took off. Not the fast crashing bounce I associate with deer, but a quick enough retreat that I wasn't concerned that Footsteps would be back anytime soon. By the time my husband arrived I had settled down in bed to read. He stayed the night with me under our pile of blankets and sleeping bag. Footsteps did not return. I survived until the early morning light lit the tent. I was happily surprised. Since then I've found this a viable option to keep me writing. Thought it is currently too cold for me to sleep over, and just a little too scary.

That's my story about getting past writer's block. What's the weirdest thing you've ever done to get your inspiration back? I'm having a short story published! Ok... so it's not as exciting as, for instance, the announcement of a new novel. (Yes I'm working on one... or two.) My kids looked at me blankly when I announced it to them and I was told, "you're an author, you get published, so what?" I'm sure if either of them decides to take up the sublime torture of writing they won't be so flippant about being published. Regardless of their opinions, I'm pretty excited about this. As the title suggests I'm being published in the, "Gasconade Review." It's a literary publication based in Belle, MO and founded by the first Poet Laureate of Belle: John Dorsey. It's put out once or twice annually and they do show a preference for Missouri writers and poets. The Gasconade Review #5 is different than the previous four in one aspect: it's an all-women collection. How could I pass up the opportunity to participate in an anthology of talented women? I couldn't, that's how. I'm excited for the release of number five since the Gasconade Review comes out in a nice book format, aren't they lovely? Sorry I'm getting distracted now.

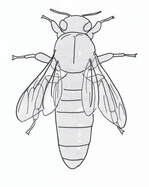

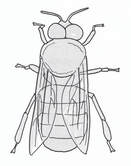

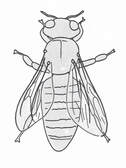

The title of my tale is, "Good Boy." I had a lot of fun writing it, because it's a little horror story based on the myths and folk tales of the black dogs in their various forms: hellhounds, barghest, churchyard grims and other spectral dogs. They are often an omen, or herald of death, but in some of the stories they exist to protect a location or, a person in need of protecting. Fun right? I could go on but I'm just going to have to leave it at that. If you want to know more, you'll just have to buy the book when it comes out. I know I don't normally write short stories. What am I doing? Why would I want to put a short story in an anthology? Aren't I a novelist? Yes, my goal is to continue writing novels, but it sure does take a long time to get a novel from the plotting notebook to the published book. I'm not going to lie; my first novel took me literally years, with an 's', as in multiple years. Who wants to wait years to read something I've written? I don't, but then, I don't have to wait years. I have to look at my writing every day. Everyone else, however, has to be patient. In case you don't want to be patient, I didn't think it could hurt to sprinkle a short story here, or there. I promise you they don't cut into my novel-writing time at all. They're what I write when I have writer's block. After all, it's better to write something than nothing at all. That being said: if you suddenly see a bunch of short stories from me, send help, it means I'm hopelessly stuck. Hi everyone! I was a guest speaker for honey bee appreciation day at the Belle Library. I had a great time mostly because I had a great audience. It was wonderful to talk about bees in front of people who seemed to love bees as much as I do. In case you wanted to be there and weren't able to come I'm going to share what we talked about: We talked about bees. Not just any bee, I was there there to talk about the cute little bug known as the European or Western honey bee, of the genus: apis mellifera. Why European bees? Why can’t we talk about good ol’ American bees? Because our American honeybees are European bees. I’m not trying to be confusing, but those European honey bees appear to have originated in eastern tropical Africa. Our local honeybees are called European bees because the ones here came to the United States with European colonists in 1622. Originally landing in Jamestown, Virginia, they spread across the country with the settlers; taking nearly two centuries to become common all the way to the west cost of the United States. Honeybees are not native to the United States. We have our own native bees and pollinators, more than 4,000 species of them, but they don’t get as much attention because they don’t offer us what the honey bee does...you know…honey. It’s important to remember that when I talk about the stressors for honey bees and what we can do to help, these things will also help our own native bees and pollinators as well. We don’t want to forget them. And just in case anyone is still hung up on the fact that I told you that honeybees originated in Africa and you may have heard about those “Africanized killer bees” spreading through the United States. Let me clear up some common misconceptions. Killer bees aren’t quite what they’re made out to be in the movies. Yes, there are a species referred to as killer bees in Africa that are more aggressive than the European honeybee; they haven’t been domesticated. The killer bees in the US are from experiments done in Brazil and have spread north all the way to the southern United States. They are much more aggressive, but not more venomous than the standard honey bee. As far as I know they haven’t made their way as far north as this part of Missouri, only because they can’t survive our harsh winters. We require slightly more cold-hearty bees. And when it comes to bees being “killers” it should be noted that ANY hive of honey bees is fully capable of killing a human. Bees are mostly only dangerous very close to the hive. Killer bees are dangerous a little further from the hive than a standard honey bee and will initially attack in greater numbers. That’s the main difference. Bees are normally pretty docile creatures. Being stung by a honey bee when you are not near the hive is extremely uncommon. No life-loving bee wants to sting anyone. A honey bee has a barbed stinger, meaning that when they sting, they have to rip off their stinger leaving it, and the venom sac behind. This will kill the bee, and I can imagine it’s would be deeply unpleasant for them as well. A bee will readily sting to defend the hive, but when they are out foraging, they generally only sting if it appears they might die. I kind of admire that, if they are going to die, they’re going to try to take you with them. So if confronted with a bee: if you stay calm, they will pretty much always leave you alone. Honey bees can be divided into more than 44 sub-species of honey bees that can vary greatly in temperament, coloration, and productivity. I don’t think it’s terribly important to get into all the different kinds of honey bees unless you plan to get your own hive. Speaking of hives, That’s something uncommon among bees in general: hives. Most species of bees are solitary. Only 10% of the world’s bees are social, and only a small percentage of those construct hives. Honey bees however, are social insects who do live in a hive, which is a highly organized social community. There are only three different kinds of bees in any honey bee hive. The queen, the drones, and the workers.

For the first two or three weeks after a newborn worker chews her way through the wax cap on her brood cell, the young worker bee cleans the brood cells starting with her own and clears any debris from the hive. Bees are very tidy creatures. During this time, she will also feed and warm larvae, and attend and feed the queen. This is why I’ve often heard them referred to as nurse bees. They also have to produce wax and draw out the new combs where their food stores, and new larvae, will be housed. They basically do all the housework. Some of these bees will guard the hive’s entrance, laying down their lives to stop any threat to the hive. When a worker is about 18 days old her duties change and she will become a scout and forager bringing back nectar, pollen, propolis, and water. These bees are the one that perform the famous waggle dance, moving in circles while waggling to communicate to the other bees the location of the best forage. The worker’s short life ends when her wings wear out and she is either unable to return to the hive, or unable to fly from it. When they are no longer able to provide for the welfare of the hive those that are still in the hive will often leave to die. I’ve seen it myself. Now that we know the purpose of the bees in the hive, we can talk about the hive itself and the way it changes over the year. In the earliest days of spring, the queen bee will start to lay eggs again after her winter break. The exact moment that this happens will vary from year, to year, queen to queen, and species to species. Unless there is particularly fair weather, they will need to use their remaining winter stores to feed all the new workers and drones. This is often when some beekeepers will feed their bees. I haven’t fed my bees in years simply because I never take so much that they can’t live off what they have stored. Normally about mid-spring bees will have regular sources to collect nectar and pollen again, creating new stores for the rest of the year. Late spring to early summer is often when my husband and I harvest honey, though a lot of people wait until the end of summer. Late spring and Summer are also swarm season. Bees go on their merry way collecting nectar, and pollen to feed the hive, collecting as much as they can. Swarming occurs when the hive is too full of either bees or honey. Remember what I said about queen bees being made from worker eggs? If the queen isn’t laying vigorously enough, or all the space in the hive is occupied, the workers will take it upon themselves to create new queens. These new young queens either take over the hive in the case of supercedure (replacing the old queen with a new one), or swarm (the process with which the hive splits.) When swarming a queen will take a large number of workers and leave the hive. The original hive continues as it had before with a smaller number of bees, and the swarm that left sets up somewhere else. When this swarm is looking for a place to live is when you will see massive bunches of bees resting in strange places. If you happen to see one of these bunches, don’t get alarmed and don’t harm them. They are as docile as they will ever be, and will likely move on soon. Swarming is how bees naturally increase their numbers in nature. Beekeepers who are raising the bees for honey don’t want this to happen, it will reduce output from a particular hive. I personally allow it to happen naturally. My hive has split many times throughout the years. I’m thankful for it because it increases the numbers of wild bees in my area. There are a lot of old sayings about the nature of honey bee swarms and when it’s fine to take them. One old saying goes like so: "A swarm of bees in May, is worth a load of hay. A swarm of bees in June, is worth a silver spoon. A swarm of bees in July, isn’t worth a fly." The reason for this is that bees needed to set up housekeeping and it was believed that a swarm found in July wouldn’t have enough time to build up the stores they needed to make it through the winter months. Which is true in this area if you don’t give them foundations and feed them, as it would be for wild bees. When autumn rolls around the available nectar and pollen wanes, before disappearing completely. This is the time that bees know that they need to put their work towards making it though the winter. Honey bees do not hibernate. Because of this they prepare for the coming winter in two ways. One is that the queen stops laying, because the workers who are with her now will likely be with the queen through the whole winter. The other thing that will be done is to remove the drones from the hive. Drones have absolutely no use in the winter, and the bees will feed only the necessary bees. For this reason every male bee will be rounded up and thrown out to die of starvation, exposure, or by being stung to death by the guards if they attempt to return. No males will overwinter in the hive. It seems harsh but if they run out of food, they’ll all die. Thousands of worker bees have already sacrificed themselves to produce that food, now the drones must do the same to maintain it. Winter has its own particular dilemma for bees. Bees are cold-blooded, so when the temperature drops in the winter, the bees will form a tight cluster around the queen. Her body temperature must be maintained at about 81 degrees Fahrenheit, all winter long. The workers around her manage this by vibrating their bodies. A vibrating worker bee can heat herself to 111 degrees but generally don’t to conserve energy. This vibration this takes a lot of food. It’s estimated that 2/3 of the honey in a hive will be used for heating. The bees on the outside of the cluster generally allow their temperature to drop to about 48 degrees before they crawl inside to warm themselves up, exposing other bees to the cold. This churning motion in the cluster allows all the bees to stay warm enough to survive the winter. When spring comes again, they will raise the temperature back up to about 93 degrees, so the queen can get back to the job of laying eggs for the new spring bees. I know that it’s all fine and good to see what bees do for each other, but as we humans often ask, "How do bees benefit us?" To start with; honey bees are the only insects that produce food eaten by humans on a commercial scale. Actually, there are five products that are produced by honeybees and used, or consumed, by humans. Can you guys name these five things? They are: honey, wax, bee pollen, propolis, and royal jelly. When people think of the honey bee, obviously they think about honey; that sweet sticky substance that’s so good on toast. Other bees can produce honey as well. Bumblebees for instance; but they only produce enough for the queen to survive the winter, nowhere near enough to feed a human. Honey bees are the only bees that make enough honey for humans to eat too. But what is honey, and how do bees produce it? Honey starts its life as nectar, a sweet watery solution collected from flowers containing a variety of substances including sugar which is a bee’s main source of energy. The nectar to produce a pound of honey requires foraging bees to fly about 55,000 miles, that’s about 2 million flowers. Each honeybee will produce only about 1/12 of a teaspoon of honey in its life. Seriously, a teaspoon of honey is the life's work of 12 bees. Bees have glands that secrete an enzyme that’s mixed with the nectar in the bee’s mouth. She will store this enzyme and nectar mixture in her honey stomach to carry back to the hive. This nectar will be delivered to the indoor bees and may be passed mouth-to-mouth from bee to bee until its moisture content is reduced from about 70% to 20%. Other times the bees will put it directly into the honey cell to allow evaporation to occur naturally from heat and air movement. When the nectar mixed with enzyme is fully evaporated it becomes what we know as honey and the bees will cap it with wax to keep it from reabsorbing water and fermenting.  The next thing people think of when it comes to bee products is normally beeswax. It’s still a widely used commodity today, being used in: furniture polish, cosmetics, pharmaceutical products, leather conditioner, coatings for candy, and all kinds of crafts and hobbies. But where does this wax come from? First a bee will feed on large quantities of honey. It’s estimated that 5.5 – 8.5 lbs. of honey are used to produce just a pound of wax. When the bee is well fed, it will cluster together with other bees and raise their temperature. In a day or so it will begin to secrete wax scales from glands on it’s abdomen. The bee will then chew on these adding saliva and other secretions to make it malleable before adding it the hexagon-shaped cells that are designed for maximum efficiency.  The next product: bee pollen is the very fine powder that collects on the bees while they are foraging for nectar. Every few flowers the bee will wipe herself down and moisten the pollen with a drop of honey and push it into pellets that will be stored in the pollen baskets on her legs. When they are full, they are visible to the naked eye on the bee’s back legs. It’s then stored in the comb as bee bread to be used by the nurse bees to feed larvae and the queen. Not as many beekeepers collect pollen. The pollen collected at the opening of a hive is different than the pollen in the comb. The pollen in the comb contains honey, enzymes, and propolis. Bee pollen is eaten by people as a health food because it is one of the richest foods in nature, containing a wide variety of proteins, minerals, fats, and vitamins. Less commonly known is propolis, or bee glue. A resinous substance collected from trees and plants. Bees use it to seal unwanted gaps in the hive, as well as coating the body of an intruder that is too large to remove who has died (such as a mouse,) to keep it from decomposing in the hive and contaminating the colony. Sometimes they even use propolis to coat the walls as a sealant to protect the colony from infection. It’s collected by bees who will chew on tree resin until it’s malleable enough to be placed in the pollen basket and carried back to the hive for use by the workers there. Historically it was used by the ancient Greeks, Egyptians, and Romans as a remedy for a number of ailments, swellings, and sores. Today is used for it’s antibiotic, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antifungal benefits. Being used for everything from wound healing to tooth care. The last, and most rare thing that humans use that bees produce is royal jelly. Isn’t that the stuff that’s used to make a worker egg into a queen bee? Why yes, I’m glad you remembered. It’s simply a thick, creamy-white liquid that’s rich in vitamins, proteins, fats, sugars, and other components. This substance is created by the nurse bees from regurgitated nectar mixed with secretions from their hypopharyngeal and mandibular glands. Because of its ability to make workers into queens it’s associated with increased energy, immune function and general longevity. For this reason, it’s added to health supplements, soaps, and cosmetics. I’m not aware of any studies proving any of these beliefs, so, the truth of the claims about royal jelly is something you’ll have to decide for yourselves. Are you amazed by what the humble honey bee offers to us humans yet? Would you be surprised to know that the items that bees produce are not even the full extent of what they do for us? What else could there possibly be I hear you gasp. Let me tell you that bees are deeply connected to more of our food than just honey. Fully one third of the food we eat requires pollinators. Do you like apples, cranberries, melons, broccoli, blueberries, cherries, beans, tomatoes, onions, carrots, almonds, and literally hundreds of other vegetables and fruits? Most of these would not exist or would be very scarce without the help of pollinators. Of the approximately $20 billion dollars worth of US crop production supported by pollinators, commercial honey bees make up about half. Wild bees and other pollinators take care of the rest. Who knew how important insects could be? After getting to explain to you how wonderful the honeybee is, I have something to tell you that might be a little hard to hear. There was a 40.7% decline in the honey bee population this last year, which is only a little bit higher than the losses the year before. Obviously, this is an unsustainable problem.

There are a lot of factors contributing to these losses in population. Varroa mite, loss of habitat, and exposure to pesticides appears to be the biggest contributions. These factors can all lead to the death of a hive or the dreaded colony collapse. Beekeepers can work to control varroa mites in their own hives, and hope the wild bees are strong enough to exist alongside these mites. What about loss of habitat? What’s causing that? Haying, grazing, demanding green weed-free lawns, and monoculture (the growing of only one kind of plant for huge stretches of land,) are all reducing the bees access to the variety of plants they need to continuously collect nectar and pollen from spring to fall. Lastly there are the dangers of pesticides and herbicides. One very dangerous herbicide glyphosate (Roundup) is the world’s most widely used herbicide, and was long touted as harmless. What a shock that something we’ve been told was harmless turns out to actually have ill effects. Glyphosates sprayed directly onto a bee is not immediately lethal to the bee, this is true, but it does disrupt and kill crucial bacteria in their gut which is necessary for their immune response. This makes them more vulnerable to lethal infections. In one study only 12% of honey bees fed glyphosate survived a serratia marcescens infection (a bacteria commonly found in beehives) compared with 47% who survived who had not been fed glyphosate. Another commonly used pesticide that is extremely dangerous to bees are the neonicotinoids. These also don’t kill the bees immediately, instead they poison them slowly over time. I read an article about how these neonicotinoids affect bees, the study of which was printed in the British Scientific Journal. Basically, it stated that when bees are offered food laced with a neonicotinoid pesticide, they begin by avoiding it, but slowly over time, they begin to prefer it, and in larger and larger doses. It targets nerve receptors in the insects that are similar to the receptors on humans that react to the addictive properties of nicotine. In other words, bees are becoming addicted to it. Now it’s one thing to have a single bee who needs its nicotine, but these bees are the foragers for a hive. They bring back all the food for the colony, and in essence poison the entire hive. California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation has released a report which concluded that neonicotinoids cause a significant risk to the bee population and that any plant that produces nectar or pollen should not be sprayed with neonicotinoids at any time. These are just two of the many herbicides and pesticides that bees have to contend with, making modern agriculture very dangerous to the bees and pollinators that it relies on. What is the federal government doing to help? The US Department of Agriculture recently announced that it has to suspend its collection of data about honey bees due to budgetary reasons. That’s what. I don’t know what the government’s plans are regarding protection of pollinators going forward, but I don’t think I’m going to count on them to fix it all for us. So what do we do? First, we need to admit that the main reason for the decline in the population of honeybees is us. There are things that beekeepers need to focus on, such as controlling varroa mites and good management practices. There are things that farmers can do such as research more sustainable methods of agriculture, set aside land that they will neither graze nor cut, and turn away from the use of pesticides and herbicides that harm our pollinators. But they aren’t the only ones who can do something. There are things that literally every person can do to help save the bees. You can decide never to use Roundup and similar weed killers again. Did you know that there are safer alternatives? No kidding. A quick internet search will yield lots of homemade weed killers. The two I use personally are boiling water, and pure vinegar. Boiling water can be poured directly on plants that you want to kill without doing any long-term damage to the surrounding soil. It’s a little dangerous but it works. The second, and safer option is pure, undiluted vinegar. Put it in a spray bottle and just spray whatever you want dead. It seems to be most effective at mid-day. Some particularly hearty plants may take several applications. Re-apply whenever you see new green growth. You will starve those roots out with persistence. The best part is that you don’t have to worry about your pets, children, or wild animals coming in contact with the vinegar. It’s food. The next thing we can do while we’re talking about that lawn, is to be less picky about having it cropped short and made up of just grass. There are many wild flowers that bees depend on that will bloom before that grass gets terribly overgrown. Dandelion and white clover are some of my favorite things to see on the lawn. As a beekeeper I to love to see kids blowing dandelion fluff around like guerrilla warfare. What’s it going to hurt to let your lawn get a little longer than your neighbor’s? Give the bees a few days with those flowers, then cut them, they’ll grow back. It’ll save you a few mowings every year and it will feed countless bees. That is just part of the effort to help restore the habitat that we’ve been stealing from our pollinators. Bees need rich diverse areas of wildflowers and other vegetation. They need to find something flowering for the entire growing season. No one plant will do that. One of the more fun things we can do is plant flowers. Bee friendly flowers that bloom in various seasons, especially early spring and late autumn when they need it most, can be planted around your home, in pots, and even in window boxes if you don’t have a lawn or patio of your own. Some subdivisions and housing developments are very strict about the lawn, but I’m not personally familiar with anyplace that doesn’t allow flowers. So have fun. Plant flowers, mow less, avoid herbicides and pesticides, and if you have the space and the courage, consider keeping a hive of honeybees at your home, or the home of a friend or family member. Maybe together we can all save the bees. It's no coincidence that the heroine of my first book was an herbalist. I been fascinated for more than a decade by the use of plants in healing. I had the pleasure recently of working with one of my favorites: the lovely St. John's Wort. St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum) This plant grows in sunny fields and can spread vigorously from short runners and as many as 30,000 seeds per plant in a single season. Unfortunately I haven't had any problems with this particular plant trying to take over. It's a hardy short-lived perennial that can be easily identified by holding the leaves up to light. They will appear to be marked with tiny pinhole dots. Harvesting should be done on a sunny day at mid-day. This herb is often ready to be picked around the summer solstice. Pick the flowering tops of the plant, flowers, buds, and leaves. It should be made into whatever formula it's supposed to be used for right away. Fresh plant is supposed to be much better than dried. St. John's Wort's most well-know use is for treating depression. But it is also commonly used for muscle aches, nerve damage, nerve pain, as a tonic for nervous system health, as an antiviral, and even as a sunscreen. CAUTION: Due to it's drug metabolizing enzymes it can cause increased metabolism of certain drugs lowering their effectiveness. This herb should be taken with extreme caution if you are taking any necessary lifesaving medication. St John's Wort is well known for having quite a few drug interactions and should not be taken with antidepressants, birth control pills (makes them ineffective), cyclesporine, digoxin, indinavin and other drugs used to control HIV, irinotecan and other drugs to control cancer, warfarin and other anticoagulants, but this is by no means the whole list. Check with your healthcare provider for any known drug interactions before you begin taking this herb. Overdose can lead to anemia and liver damage. In large quantities St. John's Wort can be a nerve toxin. Always start any herbal medication with small doses and work your way up to an effective dose. Livestock should also not be allowed to graze freely on fields of St. John's wort as the amount ingested can very quickly become toxic. After taking all due cautions into account, if you still want to use this very effective herb, the tincture is the easiest method I know for making medicine out of St. John's Wort. My second favorite method is to make an infused oil, but that's a different experience and medicine for a different day. Making the tincture is simple: First chop the flowers and upper six to eight inches of plant material: Next put this plant material in a jar. It should be packed loosely. Not so tight that you can't push your finger down through it, but not too fluffy and loose. Mark where it comes to on the jar and fill to just a bit (maybe a half inch) above that line. Sorry for how imprecise my methods are. I not very formal when I do these things. Finally label the jar with the contents because wilted plant material all starts to look similar over time. Leave the plant material in the alcohol for four to six weeks to extract, shaking daily for the first couple of weeks. It should turn a deep red. Then strain out the plant material and keep in a tightly lidded container. Tinctures have a very long shelf life, and can be used with little worry for a year or more.

|

Denise Terriah

I have an ongoing interest in dystopian fiction, both reading and writing it. I’m a fan of simple living and draw inspiration for my writing from my love of old-fashioned skills and my small hobby farm. Click on the icons below to follow me on social media: My first book is available on Amazon

Archives

January 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed